Few ‘Outsiders’ Took Part in Building of ‘New St. Paul’s

What did we talk about in 1874, just seven years into nationhood?

“What will Sir John do about Louis Riel?” An old topic had become new again. Ottawa was feeling political pressure. Riel had previously led the Metis in the Red River Rebellion and established a provisional Metis government. Ottawa chose to negotiate. Then Riel executed the Orangeman, Thomas Scott. British and Canadian forces headed west. He fled across the U.S. border. Time passed. Sentiment died down. John A. MacDonald hoped it was a permanent exile. For the sake of Quebec, he considered a pardon. But then he came back across the border! Public opinion outside Quebec suddenly coalesced. The government was forced to issue a new arrest warrant for him.

And then we shifted to another favourite topic: royal gossip: “One of the Duchess of Edinburgh’s hankerchiefs is worth 1000 pounds, and cost, for its production, five years of labour besides the eyesight of the unfortunate workman”.

Our own Rev. Smithett was more occupied these years with Sunday school teaching. Among his colleagues, he was considered an expert. He attended every Sabbath School conference to make his beliefs heard. He believed each church should generously fund the “Sabbath Schools” but did not think children should be coerced into attending. At one conference, a colleague vehemently argued that the spiritual needs of children required near-perfect attendance in Sunday school. He responded mildly but pointedly that the rural Common Schools only achieved a 50 percent attendance average, the town Common Schools only 70 percent and so the Sunday school children should be “dealt with charitably”.

In 1881, he left St. Paul’s to become Rector of Christ Anglican Church, Omemee.

Then in the spring of 1888, an epidemic of typhoid fever ran through the Omemee area. Many died of it. The good Reverend was one of those. Newspapers around the province wrote eulogies. From the Port Hope Times:

“The death. of the Rev. Dr. W. T. Smithett of Omemee, Rural Dean of Haliburton, was a shock to the region. No one in the Midland district was more widely known with more kindly feelings. He had spent 43 years in the ministry. During all these years he had not missed a service through ill-health, until his final illness.”

Again, there was difficulty choosing a new minister. The primary candidates were the 63 year-old Rev. Vincent Clementi of Peterborough and the 31 year-old Rev. Samuel Weston- Jones, just finishing his training.

Both had very interesting backgrounds.

The Rev. Vincent Clement was the son of the renowned musician and teacher, Muzio Clementi of Italy. Muzio was a colleague of Beethoven and was considered his equal at the time. Upon his death, he was buried in Westminster Abbey. Vincent grew up with servants in his household, attended Harrow and Trinity College in Cambridge and, because of his father’s fame, was inducted as a Church of England minister by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Married to Elizabeth Banks, they had two children before she died in 1848. Seven years later, Vincent and his boys immigrated to Peterborough.

The Rev. Samuel Weston-Jones also grew up with servants. He was the son of George Jones, a wealthy brush manufacturing company owner of Gloucestershire, and of Anna Juliana Bayly of Sussex. He immigrated to Canada in 1871 to join his older brother Edward who had preceded him to Canada as a minister and then entered training himself shortly after.

The solution to who would become Rector of St. Paul’s was a simple compromise. Rev. Clementi, the senior cleric, became Rector but stayed mostly in Peterborough at his primary church while Rev. Weston-Jones acted on-scene as Curate-in-Charge at St. Paul’s. Two years later in 1883, Rev. Clementi resigned and young Samuel became Rector in name as well as in practice. His significance to the life of St. Paul’s was the building of “New St. Paul’s”.

By this time, “Old St. Paul’s” was seriously deteriorating and was crowded. It was a time when church pews were enclosed and set aside for particular families. An 1884 church motion reflected the crowding issue. “Pewholders’ right to the pews extends only to what they occupy. Sidesmen may (now) sit non-pewholders and strangers in empty seats”. Outside, they were pressed in by the normal life of Lindsay. A letter to the Anglican Synod described the setting: “We have a livery stable to the southwest (now, “Joel’s Restaurant”), hotel stable to the southeast, a cabinet workshop to the east and a butcher shop to the northwest”.

The congregation was divided. Some wanted to repair and expand their beloved church while others were ready to sell it and use the funds to build a larger church in a quieter area. Frustration burst out. Thankfully, Rev. Samuel Weston-Jones and a core group of steady church leaders spoke frequently enough about compromise and consensus and prayed often enough for collective wisdom that a path forward was found that gained widespread acceptance.

Financing, though, was still an issue. A new church would cost about $20,000. They asked Synod in Toronto for advice and financial help. They wrote back: “Synod has no power to mortgage. We recommend you purchase another property, vest it (the property) in Trustees, borrow through them and possibly sell a portion of the present land”. A great thought, but finding another large property off the main street but still near by would be expensive.

An answer emerged. The man who received Synod’s letter was Adam Hudspeth, born in Cobourg, local lawyer, parishioner of St. Paul’s, often a churchwarden and later, a Member of Parliament. His wife, Harriet, born in the Northwest Territories, was a capable, unique person. After a private discussion together, Adam came forward to donate a three quarter acre piece of land on Russell Street, one block directly south of the existing church. Later, an adjacent half-acre to the east was purchased for a future parsonage.

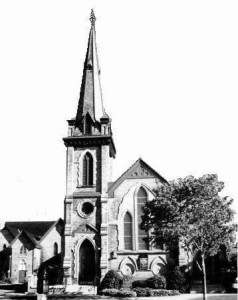

Francis Darling of Toronto was chosen as the architect for “New St. Paul’s”. Few other “outsiders” took part. An amazing number of Lindsay and area residents provided material or helped build it. McNeely and Walters of Lindsay received the contract to build the 110x 50 foot modified gothic-style church. Local stonemasons built the foundation with Bobcaygeon stone and faced the front and tower with Ohio blue stone. Fox Brothers and Francis Curtin, brick makers of Lindsay, provided the white brick for the walls. Local workers tenderly mounted the “cathedral glass” stained glass windows. Alexander Cullon, a Lindsay blacksmith with unique artistic skills, fashioned the beautiful hammered finial above the 50 foot tower capped by a 60 foot spire. Inside, E. Woods & Son inserted the gas lighting equipment, William Howe & Son, Tinsmiths, installed the two giant hot air furnaces, Fred Reeves and two of his sons, Wesley and Samuel, were the plasterers while Leonard Newton and Alexander Skinner took over as the painters.

But in May, 1885, before the first stone was even laid, Harriet Hudspeth, who had put so much of her own vision into the new church, passed away.

Six months later, “New St. Paul’s” officially opened on November 25th with a major dedication service. Many clergy took part. The Bishop of Toronto was there. The morning service was packed; so was an afternoon service of confirmation and the evening service was “crowded to its utmost capacity”. The sermon focused on the value of good works; a fitting conclusion to years of effort by those who had built this church.

While “New St. Paul’s” prepared for its future, Lindsay was also primed for change.

‘Old St. Paul’s” still stood on a main street in transition. New businesses were moving in. Kent Street needed serious upgrading. Old tile drains were in deep trouble. Town Council learned the public outlay would be $2000 and the private expense to the store owners even greater. Some wanted to proceed; others demanded stop-gap measures that required store toilets to empty into backyard privies instead of town sewers. The “stop-gappers” won and that summer’s repair season was hectic.

Telephones had come to Lindsay but the infrastructure was sometimes dangerous.

“On William St. between Peel and Wellington, a coil of (telephone) wire dangling from a pole caught a rig going under it .. and nearly pulled the occupant out of the buggy before the horse could be stopped”